Last year, I shared a select few essays from my time as an MA student at King’s College London in 2023(MA International Political Economy). I have decided to publish the remainder of those essays now on my blog.

This essay was the second of two pieces for the ‘core’ module of the course, concerned mainly with the theory of political economy and its applications. My thanks goes to Dr Thomas Purcell for facilitating the course and putting up with my often stupid questions in seminars.

This was one of my lower graded essays from the year, but still, I like this one.

Introduction

This essay takes a neo-structuralist stance to show how extractivism occurs on a global scale and is promoted by global capitalist dynamics. Ultimately it aims to show how extractivism has become so pervasive that it can function as an organising concept for contemporary capitalism.

By identifying it as a force with global implications pervasive at all levels of the economy in all regions of the world, this essay argues extractivism is adequate as an ‘organising concept’ for contemporary capitalism. This assertion is with limits, acknowledging that contemporary capitalism is not synonymous with extractivism. It does however encompass so much of modern economic structures as to effectively analyse the most pressing political economy issues of the day, including uneven development and impending global environmental collapse.

This essay begins with a discussion of what an ‘organising concept’ is, and what analytical value it provides. It then considers the literature on extractivism to identify how broad a definition is suitable to consider it one such organising concept. The UK is identified as a power centre in global extractivism, home to an economy which is predominantly extractive through its pervasive rentier activities. It finds that extractivism as an organising concept must be rooted in analysis of state and international actors, and highlight international power inequalities, especially between the global north and south.

Extractivism as an organising concept

This section takes Chagnon’s (et al, 2022) stance on extractivism as an ‘organising concept’ to explore the extent and limits of the term. It finds that a conceptualisation only encompassing natural resource exploitation is insufficient and a wider representation is more useful as an analytical tool. An ‘organising concept’ must however retain limitations as too large a conceptualisation removes the possibility for guiding analysis.

Organising extractivism

Chagnon (et al, 2022) presents ‘global extractivism’ as ‘a way of organizing life’. It represents “ecologically destructive processes of subjugation, depletion and non-reciprocal relations (…) diametrically opposed to the concept and practices of sustainability”. The components of extractivism are identified as: appropriation of natural and human resource wealth; a damaging drain, depleting a source irreversibly; premised on capital accumulation and centralisation of power, and creating power disparities and alienation.

This transition to a global extractivism, according to Chagnon depicts the formation of a way of organising life – a shift to becoming an ‘organising concept’. This represents a framework which synthesises interrelated concepts under one body of thought. (Chagnon et al, 2022; Wallerstein, 1984).

Wallerstein treated development as an organising concept, arguing that it be treated less as a core ideology of western civilisation and social science, and more “the central organizing concept around which all else is hinged” (1984). His view is however a mis-framing. His argument revolves around the state as the base unit of analysis for all social sciences, even arguing that in anthropology the tribe effectively functions as a state. Wallerstein thus reminds that analytical concepts can be stretched too broadly.

Development fares better as an organising concept specifically to political economy, where a structuralist approach is more valuable than to the social sciences in their entirety, but it remains too policy-oriented to adequately conceptualise modern capitalism. Better would be a concept that explicitly analyses processes, both political and productive.

Competing extractivisms

This section explores the varying conceptions of extractivism in the literature, attempting to show the implications of defining it in too narrow or too broad terms. This leads to the following section which aims to present a concept of extractivism firmly rooted in the tenets of political economy.

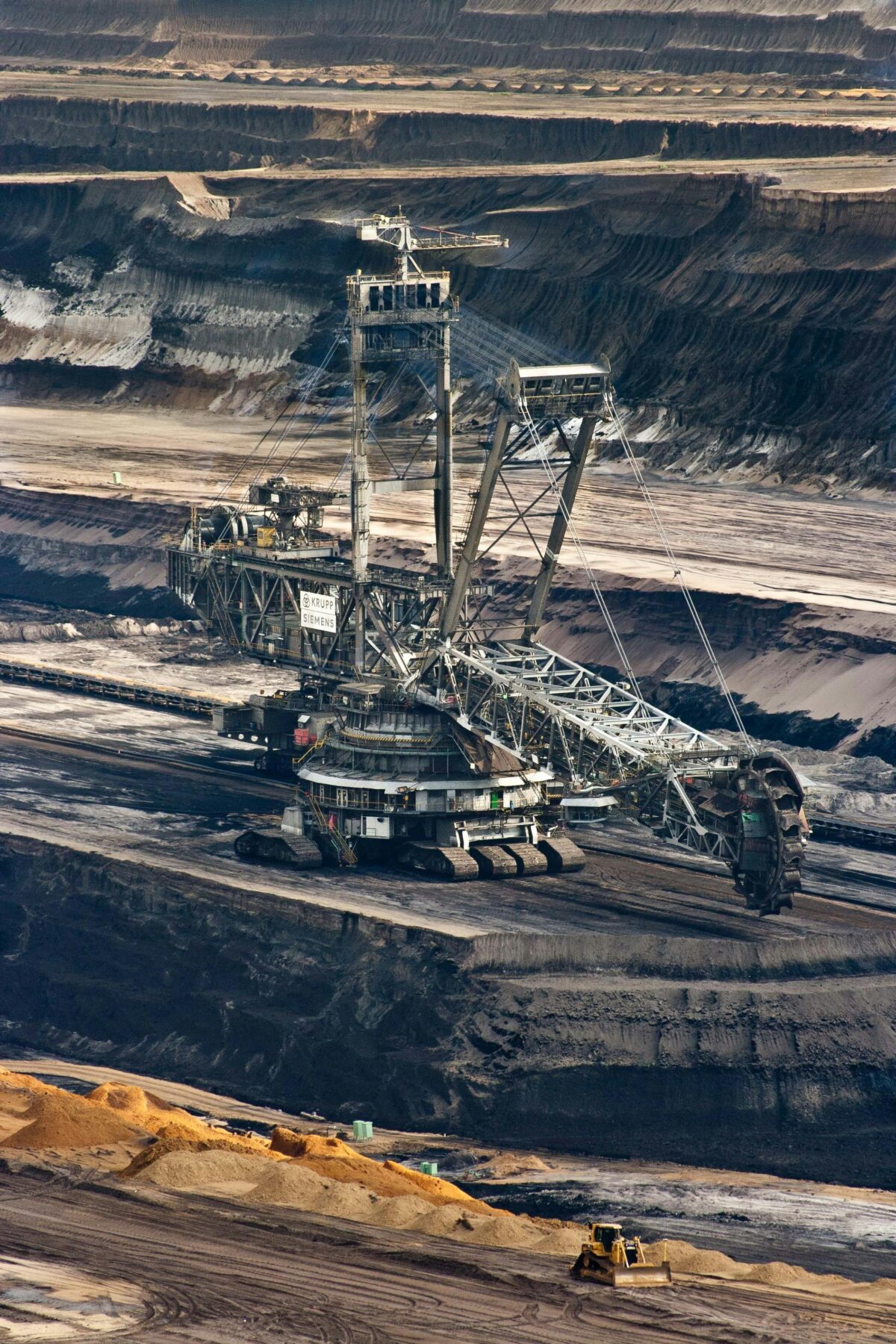

Gudynas (2018) limits extractivism to natural resource exploitation only: This is focussed on mining, oil production and monoculture agriculture. Gudynas has a different framing to other authors, talking of extractivism being ‘promoted’ from the 1970s onwards. From his perspective this occurred twofold – firstly through the TNCs and multilateral organisations pushing neoliberal logics onto Latin America, and secondly by rounds of domestic governments adopting ‘progressive policies’ in line with this logic. The result was the expansion of resource extraction and primary commodity exports.

There is a degree of naivety in Gudynas’ analysis, which differentiates extractive activities by their intensity. Organic food falls within ‘low intensity’ and irrigation processes are labelled ‘high intensity’. He evidently takes an anti-technology stance, where technological fixes are assumed to be more damaging than simple or traditional methods. While acknowledging that irrigation can be destructive, Gudynas’ clear differentiation is not necessarily always true – organic farming can be an extremely intense process.

Gago and Mezzandra (2017) attempt to expand the view of extractivism in Latin America to also include finance and financialisation. A connection is identified with exploitation through concepts such as “the hegemony of rent, the persistence of primitive accumulation, and accumulation by dispossession”. They also point out that extraction of labour is a widespread phenomenon – which at its most extreme still resembles slavery (Byler, 2022; Natarajan et al, 2019).

Arboleda’s (2020) identified forms of extractivism are as limited as Gudynas but show more clearly the implications of extractivist processes for labour. His Marxian vision of the ‘planetary mine’ removes the gloss of globalisation, maintaining the transnational forces of GVCs and their associated connected infrastructures remain, but argues they now exist in tandem with militarised borders and increasingly ethnocentric nationalism. It goes a long way in explaining the geospatial dynamics of contemporary capitalism and its detrimental effects on labour through fragmentation and disempowerment, while rooting this process in extractivism.

Gudynas (2018), while arguing for too narrow a definition of extractivism, was right to posit that too wide an abstraction dissolves analytical value. The value of an ‘organising concept’ thus comes from reaching a maximal point that frames but does not allow superfluous factors.

Dunlap and Jakobsen (2020) offers one such approach blown out of proportion through their conceptualisation of extractivism as a metaphysical ‘Worldeater’. The authors intentionally mythologise extractivism as a metaphysical force. The Worldeater is an abstraction of an abstraction, at its most connected merely linking extractivist logics to human civilisation as a whole. This is ahistorical, failing to recognise the roles of colonialism and the historical development of capitalism in giving impetus to extractivism.

The logical endpoint of their analysis is that extractivism is part of how human beings operate and that the more humans exist the more extractivism, regardless of socio-political context. Extractivism would not be able to be displaced spatially, and yet the developing world evidently takes the brunt of its damage. Historically, it is organised human agency and its demands on resources which propels extractive activities (see Brett and Foster, 2013; Malm, 2012; Parson and Ray, 2018) and the widely accepted emergence of the Anthropocene proves this (Steffen et al, 2011; Steffen, 2015).

Briefly returning to Wallerstein (1984): “One can state or discover ‘universal’ laws about any phenomenon at a certain level of abstraction. The intellectual question is whether the level at which these laws can be stated has any point of contact with the level at which applications are desired”. Creating a macro-mythology in order to encompass all factors such as Dunlap and Jakobsen (2020) do serve to remove its analytical value. The next section therefore focusses specifically on the interrelation between extractivism, state and transnational actors, closer aligned to Chagnon (et al, 2022) and Ye (et al, 2019).

A political economy of extractivism

As a lens oriented only towards natural resources fails to encompass the full dynamics of extractivism, our organizing concept must be expanded. This must be done with a view to core interests of political economy so as not to broaden the view to a level where no analytical value can be drawn. The following section considers authors in more depth who have broader conceptualisations of extractivism and have organised it through power relations.

Chagnon (et al, 2022) emphasise but do not limit the material link of extractivist processes to natural resources and land: “The depletion of raw materials, natural resources, land and soil degradation, climate change, species extinctions, biodiversity loss, and deforestation, are wedded to capital accumulation and the drive for continued exponential growth of the world economy.” They attempt to move the debate from extractivism to global extractivism, arguing that it has become an all-pervasive structure affecting the lives of most human beings. This occurs through varying processes, all falling under the remit of extractivism. These include through GVCs, rentierism, pollution, energy production and consumption and biodiversity loss. Our existing global political and economic structures encourage extractivist accumulation, the authors referring to both the global financial system and the drain of natural and human resources from global south to north.

Ye (et al, 2019) recognise physical extraction of natural resources through mining, fossil fuel extraction and agriculture as a commonly accepted conception of extractivism. They contest however this as being inclusive of all forms of extractivism and propose a politico-economic understanding that structures “the processes of production and reproduction.” An operational centre controls the flows of material and wealth but does not contribute to their value creation – it takes away value without adding anything itself. This insistence on a politico-economic understanding of extractivism is essential when considering whether it enables us to analyse capitalism as a whole.

Defining extractivism purely in terms of an activity is inadequate. What is important is how it is organised. Ye (et al, 2019) argue that the following socio-political factors create the conditions of extractivism: A monopoly over resources; close linkages between state and private actors; enabled by infrastructure development; the existence of an ‘operational centre’ drawing resources from poor to rich through a chain; a process of production without reproduction, andresulting windfall profits, explaining the ‘boom-bust’ cycle of extractivism (see Veltmeyer and Bowles, 2014).

While this essay accepts much of Ye’s (et al, 2019) conceptualisation of extractivism, it argues that production without reproduction requires nuance. Finance is often treated as extractivist, as does this essay. Finance appears however to reproduce itself – new credit is born so long as there is demand. It is ultimately, no matter how abstractly, attached to material assets. “Extractivism is thought to stop when the resource base is depleted” (Ye et al, 2019) and financial extractivism exerts a parasitic nature where it replenishes itself only by moving onto a base note yet depleted. The extractive element comes from undervaluing material components of the value chain and overvaluing later through concurrent ‘value-added’ stages.

Chagnon’s (et al, 2022) vision perhaps allows for a wider field for analysis of extractivism, able to branch to studies closer to anthropology and sociology, but a political economy analysis benefits from the more explicit connection to forces of production and centres of power that Ye (et al, 2019) offers. Chagnon emphasises the importance of a central operator for extractivist activities less and underplays the link between state and private actors.

The extractivist-state-TNC nexus and power

The essay has thus far stated that extractivism is as much a power system as it is an economic one, but done little to show how. Linked to state agency in extractivist relations, extractivism becomes not only an exertion of state power but also a driver of it, the state and transnational actors collectively forming a power nexus.

Arendt (1968) argued that power is a means to an end and that social organisation based only on power disintegrate in the face of stability. Total security would reveal that community to be based on nothing but coercion. A state must therefore endlessly accumulate power to maintain the illusion of status quo. Schwartz’s (2019) work on US dollar centrality shows this in practice in economic structures, as financial dominance feeds into US hegemony. Veltmeyer (2020) meanwhile shows how the same process leaches resources out of the global south.

In principle, profit is also only a means to an end, but it doesn’t stop the wealthy from hoarding it. The flow of hard and extractive power is however different. In militaristic state power, outside states are presented as risks. In extractive economic power, outside states are presented as opportunities. Transnational extractive forces thus play a role in domestic stability in the global north, allowing for inflated incomes relative to commodity exporters at the start of the supply chain.

Arrighi (1994) contrasts political and economic power, suggesting that where the capitalist aims to draw profits from wherever they can and to accumulate capital, the politician is concerned with sustaining power relative to other states. However, this differentiation is insignificant, and they amount to facets of the same dynamic. Wealth is always relative and indeed needs to be to have any ‘value’. What makes profit valuable is its proportion relative to the profits of others. Differentiating political and economic power too far fails to identify their relationship, political power feeding economic.

Petras and Veltmeyer (2014) emphasise the role of MNCs in the ‘resource grabbing process’, as well as the influence of powerful states at the centre of the world system. These MNCs have advanced ‘extractive capital’, supported by a small number of powerful imperialist states. A new dynamic of capitalist development has emerged out of this process, creating groups and interests both in support and in resistance to it. According to their analysis this represents a political project designed to reignite slowing economies of powerful nations. The promotion of ‘forces of economic freedom’ such as private property and the market leads wealth and power back to the centre.

There are limits to this statist view of extractivism and a core periphery analysis only shows part of the picture. Girvan (2014) shows how class plays a significant role in extractive dynamics. A structuralist, state actor-only vision underplays elite influence within a state. Girvan also points out that intermediaries have always played a role in extractive imperialism. Neo-structuralist analysis underplays the role of domestic policy decisions (Saad-Filho and Weeks, 2013) such as ground rents (Purcell et al, 2016) can have on negating the value of ISI development strategies.

In contrast to both Girvan (2014) and Petras and Veltmeyer (2014) who places much weight on the power of the MNC, Ye (et al, 2019) argue that there is a trend towards centralised control of natural resources globally. One could argue that the five years between these publications saw a trend develop towards greater state control in extractive activities. Ye (et al, 2019) designated infrastructure development as one of their tenets of extractivism and China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which was only at a nascent stage at the time Petras and Veltmeyer (2014) published, had become an evident example of state centralised MNC networks by the time Ye (et al, 2019) had published.

Hickel (et al, 2021) show the scale of wealth appropriation from the global south to the global north in only one year, 2018. The authors state that this amount, 2.2 trillion USD, would have been enough to end global extreme poverty 15 times over. They emphasise the role of the IFIs in enabling this through the imposition of SAPs. Instead of assisting development, SAPs and foreign aid have often become ‘reverse aid’ where the agreements disproportionately benefit the donors. In the case of Brazil, SAPs have resulted in redistribution of land to the wealthy and displacement of smallholders and landless peasants (Petras and Veltmeyer, 2002). Harvey (2003) goes as far to argue that SAPs intentionally bring countries into subservience to the global north.

Pulling all into extractive capital

As Arendt (1968) theorised the outward force of maintaining political power, Luxemburg (2003) recognised the pull of economic power. She argued that capitalism requires outside non-capitalist territory that can be exploited to renew the capitalist centre. This would inherently be an extractive process.

Harvey (2003) captured this dynamic through his concept of accumulation by dispossession: “What accumulation by dispossession does is to release a set of assets (including labour power) at very low (and in some instances zero) cost. Over-accumulated capital can seize hold of such assets and immediately turn them to profitable use” (Harvey, 2003). This offers an explanation for the process of centralising power through TNCs and IFI policy that Chagnon (et al, 2020) and Ye (et al, 2019) identify as essential to global extractivism.

Harvey (2003) emphasises however the role of finance more strongly, placing financial activities at the heart of the process. Violent financial structures and processes and the use of them to dispossess and accumulate power is “what contemporary capitalism is all about”. This is conflated by the proliferation of property and IP rights and increasingly universal commodification of resources. Harvey suggests further that financial crises may be orchestrated to create a devalued commodity somewhere in the world to appropriate in the centre.

The hegemony of financial capital (see Schwartz, 2019) has damaged economic and social structures domestically in the US, the world centre of financial power. Industry has deteriorated and wealth distribution has become increasingly uneven. The ensuing ‘hollowing out’ of the middle class has excluded a portion of society from both capitalist production and consumption that previously was integral to domestic growth (Petras and Veltmeyer, 2014). Extractive foreign policy thus offers a ‘spatial fix’ (Harvey, 1981).

The costs of maintaining US empire (in military spending sense) is too high and unsustainable, yet this is where money is oriented in order to defend extractive interests if necessary. In the 2013 budget, fixed and procurement costs of military (and military adjacent) government spending was equal to collected personal tax revenues. (Petras and Veltmeyer, 2014).

This context of unproductive economy and geopolitics builds a logic for external resource extractivism. On one hand extractivism is a profit boosting exercise and an opportunity for governments to extract rents, but on the other it acts as a partial fix for a failing world economic structure.

The UK as an extractivist rentier centre

The previous sections clarified how financial dependencies can manifest as a form of overarching extractivism. Drawing from Christophers (2020), the following case study shows how the UK economy has become increasingly extractive through widespread rentierism. It highlights how this is inherently part of world economic systems and as such lends weight to the thesis that extractivism functions as an organising concept.

Rentierism is a form of extractivism that emphasises the monopoly element in Ye’s (et al, 2019) definition. Christophers (2020) differentiates between non-rentier and rentier activities as a difference in ‘doing’ or ‘having’. According to him, the UK economy has always been oriented towards ‘having’, firstly through agrarian land ownership, and now through financial assets. This was even the case during the industrial revolution, where wealth was predominantly accumulated in land ownership and not production.

Even industries that may not immediately appear as rent-earning in practice are: manufacturing tends to include a significant contractual and IP element; IT is built in IPR and subscription services that are a form of contract. Rentier institutions are so pervasive that the top 30 companies on the London Stock Exchange all have rentier operations (Christophers, 2020). “Rent, it can be clearly seen, is what the market values” (Christophers, 2020).

Christophers (2020) argues that policy determines what extent extractive rentierism can exist. State policy determines for example how IP infrastructure develops or whether to deregulate banks. It falls on the state to set the rules of the economic game. The rise of UK rentierism corresponds with the rise of neoliberalism, flourishing with the assistance of the neoliberal tenets of monetary and fiscal governance, and property rights. The Financial Times stated the UK form of neoliberalism has created a ‘rentier’s paradise’ – and rentierisation has proliferated as a result (Ford, 2017).

UK gross capital formation has shrunk dramatically since the instigation of neoliberal policies from the 1980s onwards. While in 1974 it accounted for 28% of GDP, gross capital formation had fallen to 19% by 1993, a level at which it remains today. It dropped even lower during the global financial crisis (World Bank, a). Profits are instead funnelled towards shareholders. Since the 1990s, dividend payment growth has increased rapidly while real wages have stagnated (Common Wealth, 2022), representing a shift in wealth to financial rentiers over wage earners. Adjusting for inflation, labour compensation for UK households increased by 25% between 2000 and 2019, compared to 142% growth in dividend payments.

This is however only the internal relationship to a global structure. The UK’s long-standing current account (World Bank, b) highlights its reliance on imports. In 2022, the UK fell to its worst trade deficit on record (Romei, 2022). This is a direct result of UK industry shifting overseas through GVC networks. This phenomenon has led the UK to become an organisational centre for extractivist capitalism (Chagnon et al, 2022; Ye et al, 2019), with finance capital as the centre of power (Girvan, 2014; Schwartz, 2019).

Observing the 10 largest UK companies by market capitalisation, nearly all are extractive rentier MNCs (IG, 2020). In the case of BHP, RioTinto and BP, they are instigators of natural resource extractivism exerting economic and environmental pressures in countries at the bottom of their value chains. Recalling analysis from Petras and Veltmeyer (2014) ‘forces of economic freedom’ including property rights and liberalised markets leads wealth and power back to the centre “to reignite slowing economies of powerful nations”. The UK extracts the global south to feed its own markets.

It is not simply the industries of major UK MNCs which are extractive, but the nature of GVCs often leads to extractive practices within the chain. A case in point is China, which became a source of ‘cheap labour’ for western nations including the UK during its ‘opening up’ period (Malm, 2012). Labour should be treated as a resource and as such this ‘cheap labour’ was a clear example of labour extractivism. In recent years this has exacerbated to the point of becoming a human rights issue in China’s Xinjiang province (Byler, 2022). The UK gains from the ‘value added’ stages later in the value chain which tend to revolve around intellectual property and contractual arrangements – added value in having rather than creating.

While some UK companies producing goods in China are there due to operational convenience (for beverage company Diageo, Baijiu production makes little sense in the UK (Diageo, n.d.)) the key advantage for a company such as Unilever for basing manufacturing in China (Bloomberg, n.d.) is a reduction in labour costs. It is therefore false to claim the proliferation of MNCs is purely to extract cheap labour, but it is also clear that they feed heavily into global extractivist structures.

It is important also to address the financial elephant in the room. London is one of the world’s major financial centres, and therefore a focal point in global capital flows. Finance is an essential part of the modern economy, but it is only productive in as much as it enables investment in other industries, a fact that led Keynes to infamously call for the ‘euthanasia of the functionless investor’ (Keynes, 1936). This group so disdained by Keynes has made a striking revival in the UK, evident in the rapid rate that UK bank assets have grown compared to lethargic GDP growth. In 1990, bank assets were slightly higher than GDP, but by 2018 they had reached over two and a half times GDP (Christophers, 2020). London’s financial sector has therefore quickly become financially extractivist since the beginning of the neoliberal era.

The UK thus exerts extractivist force both domestically and internationally, propelled by neoliberalism but also through a much longer tradition of valuing the exploitation of asset ownership over production. It is one the global centres of extractivist power.

Conclusion

This essay has argued that that extractivism is such a pervasive force in the global economy that it can be used as an organising concept for contemporary capitalism. While it is naïve to believe that any framework can truly encompass the entire nature of capitalism, an organising concept of extractivism manages a sufficient enough proportion of its core dynamics as to ensure the concept serves its analytical purposes.

This essay firstly identified precisely what is meant by an ‘organising concept’ and used this as a base to map the principles of a political economy of extractivism. This by definition must give precedence to better understanding power dynamics, especially the generation and flow of power between states and international actors. The essay found that definitions of extractivism limited to natural resources fail to account for how finance and rentier activities also follow extractive dynamics. It also critiques authors who have forced the concept too far into nebulous territory, losing all analytical value. The essay attempted to show how the logics of extractivism compel economic agents to continuously search for more sources of extraction, resulting in a downward spiral of resource and environmental degradation.

Bringing attention to the UK over a more traditional analysis such as mining extractivism in the global south enabled this analysis to show how extractivism far surpasses natural resource exploitation. The rentier activities of extractivism’s power centres are indeed integral to the continued natural resource and therefore wealth extraction from the global south. From this perspective finance, property, and contractual agreements can all be considered extractive, depleting resources overseas while simultaneously distributing wealth to a smaller group domestically.

Bibliography

Arboleda, M. (2020). Planetary Mine: Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism. Verso.

Arendt, H (1968) Imperialism: Part Two of the Origins of Totalitarianism, New York: Harcourt Publishers

Arrighi, G. (1994) The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origin of our Times. Verso.)

Chagnon, Christopher W., Francesco Durante, Barry K. Gills, Sophia E. Hagolani-Albov, Saana Hokkanen, Sohvi MJ Kangasluoma, Heidi Konttinen et al. (2022) From extractivism to global extractivism: the evolution of an organizing concept. The Journal of Peasant Studies. 49(4). pp.760-792.

Brett, C., and J. B. Foster. (2013). Guano: The Global Metabolic Rift and Fertilizer Trade. In Ecology and Power, pp.84–98. Routledge.

Bloomberg, (n.d.). Unilever China Co Ltd. Retrieved from: https://www.bloomberg.com/profile/company/ABOUSZ:CH?leadSource=uverify%20wall. (accessed 20 April 2023.)

Byler, D. (2022). Factories of Turkic Muslim Internment. In Byler, F and Loubere, N (Ed.), Xinjiang Year Zero. ANU Press. pp.163-172.

Christophers, B. (2020). Rentier Capitalism: Who owns the economy, and who pays for it?. Verso.

Common Wealth. (2022). The Great Divide: Examining Labour Compensation and Dividend Growth. Retrieved from: https://www.common-wealth.co.uk/publications/wages-and-dividends. (accessed 20 April 2023).

Diageo. (n.d.) Diageio Asia Pacific. Retrieved from: https://www.diageo.com/en/our-business/where-we-operate/asia-pacific. (accessed 20 April 2023).

Dunlap, A., and Jakobsen, J. (2020). The violent technologies of extraction: political ecology, critical agrarian studies and the capitalist worldeater. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ford, J. (2017). Lax regulation has turned Britain into a Rentier’s Paradise. Financial Times.

Gago, Verónica, and Sandro A. Mezzadra. 2017. A Critique of the Extractive Operations of Capital: Toward an Expanded Concept of Extractivism. Rethinking Marxism. 29(4). pp.574–591.

Girvan, N. (2014). Extractive Imperialism in Historical Perspective. In Petras, J., and Veltmeyer, H. (Ed.) Extractive Imperialism in the Americas: Capitalism’s New Frontier. Brill.

Gudynas, E. (2018). Extractivisms: Tendencies and consequences. In Reframing Latin American Development. Routledge.

IG Group. (2020). Top 10 largest UK companies by market cap. Retrieved from: https://www.ig.com/uk/news-and-trade-ideas/top-10-largest-uk-companies-by-market-cap-190715. (accessed 20 April 2023).

Keynes, M. (1936). The general theory of employment interest and money. Macmillan.

Luxemburg, R. (2003). The Accumulation of Capital. Routeledge.

Malm, A. (2012). China as chimney of the world: The fossil capital hypothesis. Organization & Environment. 25(2). pp.146-177.

Natarajan, N., Brickell, K. and Parsons, L. (2019). Climate Change Adaptation and Precarity across the Rural–Urban Divide in Cambodia: Towards a ‘Climate Precarity’ Approach. Environment and Planning: Nature and Space 2(4). pp. 899-921.

Parson, S., and Ray, E. (2018). Sustainable Colonization: Tar Sands as Resource Colonialism. Capitalism Nature Socialism 29(3). pp.68–86.

Petras, J. and Veltmeyer, H. (2002), Age of Reverse Aid: Neo-liberalism as Catalyst of Regression. Development and Change. 33. pp.281-293.

Petras, J., and Veltmeyer, H. (2014). Extractive Imperialism in the Americas: Capitalism’s New Frontier. Brill.

Purcell, T. F., Fernandez, N., and Martinez, E. (2017). Rents, knowledge and neo-structuralism: transforming the productive matrix in Ecuador. Third World Quarterly, 38(4), pp.918-938.

Purcell, Thomas F. 2021. Contesting Total Extractivism: Between Idealism and Materialism. Journal of Agrarian Change. 12458.

Harvey, D. (1981). THE SPATIAL FIX – HEGEL, VON THUNEN, AND MARX. Antipode. 13(3).

Harvey, D. (2003). The New Imperialism. Oxford University Press.

Hickel, J., Sullivan, D., and Zoomkawala, H. (2021). Plunder in the Post-Colonial Era: Quantifying Drain from the Global South Through Unequal Exchange, 1960–2018. New Political Economy.

Romei, V. (2022). UK’s yawning current account raises financing risks. Financial Times. Retrieved from: https://www.ft.com/content/b784e8ae-b962-43dd-a0f3-4cd163ff3314. (accessed 09 April 2023).

Saad-Filho, A., and Weeks, J. (2013) Curses, Diseases and Other Resource Confusions, Third World Quarterly, 34(1). pp.1-21.

Schwartz, H. M. (2019) American Hegemony: Intellectual Property Rights, Dollar Centrality and Infrastructural Power, Review of International Political Economy. 26(3), pp.490-519.

Steffen, W., Grinevald, J., Crutzen, P., and McNeill, J. (2011). The Anthropocene: Conceptual and Historical Perspectives. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 369 (1938). pp.842–67.

Steffen, W., Broadgate, W., Deutsch, L., Gaffney, O., and Ludwig, C. (2015). The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration, The Anthropocene Review, 2(1), pp.81-98.

Veltmeyer, H., and Bowles, P. (2014). Extractivist resistance: The case of the Enbridge oil pipeline project in Northern British Columbia. The Extractive Industries and Society, 1(1), pp.59–68.

Wallerstein, I. (1984). The Development of the Concept of Development. Sociological Theory.

World Bank, A. (n.d.). Gross capital formation (% of GDP) – United Kingdom. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.GDI.TOTL.ZS?locations=GB. (accessed 09 April 2023).

World Bank, B. (n.d.). Current account balance (% of GDP) – United Kingdom, United States. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BN.CAB.XOKA.GD.ZS?locations=GB-US&most_recent_value_desc=false. (accessed 09 April 2023).

Ye, J, van der Ploeg, J. D., Schneider, S., and Shanin, T. (2019). The Incursions of Extractivism: Moving from Dispersed Places to Global Capitalism. Journal of Peasant Studies. 47(1). pp.155–183.