Last year, I shared a select few essays from my time as an MA student at King’s College London in 2023(MA International Political Economy). I have decided to publish the remainder of those essays now on my blog.

This essay was one of two written for the ‘core’ module of the course, concerned mainly with the theory of political economy and its applications. My thanks goes to Dr Thomas Purcell for facilitating the course and for putting up with my often stupid questions in seminars.

The original question for this essay: Critically assess whether the neoclassical economics’ analysis of capitalism is a valid foundation for International Political Economy.

This essay argues that neoclassical economics has a place within the field of IPE but is limited in its applications due to inherent assumptions that conflict with sociological fields of study. IPE is an eclectic sociological field, drawing on insights from within and outside the standard realm of political science. Neoclassical economics is at its heart a study of individuals. While some approaches attempt to aggregate them to draw conclusions for groups on a social level, these aggregates tend to be built on unrealistic assumptions. This essay outlines both differences between the fields and how they interact. It analyses two areas of scholarship where political economy and neoclassical economics merge – trade relations, and behavioural economics – and evaluates whether they are coherent approaches.

What constitutes a ‘foundation for IPE?’

Almost since the conception of the field, there have been two dominant denominations within IPE, the American and British schools. The US approach is more positivist and draws more heavily on the neoclassical tradition, aiming for a ‘scientific’ structure for the field. British IPE is more normative and eclectic. Cohen (2007) and Ravenhill (2017) argue that for their differences, the British and American schools complement each other, and neither is inherently superior. This does however lead to an inherent identity problem for IPE, one that clouds the aims and approaches of the field.

According to Cohen (2008, pp.16) “IPE at its most fundamental…is about the complex interrelationship of economic and political activity at the level of international affairs”. In this understanding, IPE is strongest when eclectic. Cohen’s definition specifies the topic of the field, but assumes no particular methodology. In practice, this is representative of the IPE literature, which draws on a historical plethora of approaches, including but not limited to Liberalism, Marxism, Keynesianism and Postcolonialism.

The American school draws heavily from neoclassical economics, a fact that many colleagues in the British school are sceptical of. In their history of the transition from political economy to ‘economics’, Milonakis and Fine (2009) note that neoclassical economics has become increasingly esoteric, infatuated with their models and rejecting all that cannot fit within them. The authors do not doubt the position of this thought within the history of political economy, but lament that it has taken prime position, treated as doctrine and truth.

Others see significant advantages in neoclassical approaches. Gilpin (2011) considers neoclassical economics to be the more rigorous and theoretically advanced field in comparison to political economy. He believes that by combining the narrow lens of neoclassical economics with the more intuitive and history-led methodology of political economy, a more profound understanding of economic affairs can be formulated. According to Gilpin (2011), the fields diverge only in “the questions asked and the answers given” and that there is no necessary conflict in conclusions.

To answer whether neoclassical economics can serve as a foundation for IPE, it is important to establish whether its core assumptions are suitable for sociological and political study. Given a large body of IPE research does utilise a neoclassical logic, it is also important to ask whether its methods can be employed for certain tasks or for part of a wider reaching methodology.

Contrasting neoclassical assumptions with IPE

This section explores how the three core tenets of neoclassical economics identified by Arnsperger and Varoufakis’ (2006) interact with IPE approaches. These three general rules, according to the authors, hold true for all neoclassical scholarship regardless of the time or subfield that it falls into: Methodological individualism, instrumentalism and equilibration.

Analysing social structure

According to Foley (2008), neoclassical economics is based on utilitarian philosophy, and “admits no social category that transcends individual action, or the simple combination of individual actions” (Foley, 2008). Classical political economy is in contrast a field with its roots firmly in sociological traditions (Foley, 2008).

Critiques of neoclassical economics have in the past criticised its assumption that economic agents are rational actors. Arnsperger and Varoufakis (2006) argue that criticising neoclassical models for assuming perfectly informed, rational actors no longer holds as models increasingly account for the more realistic irrational actor (Arnsperger and Varoufakis, 2006). What is true however is that neoclassical thinkers assume that actions must be taken at the level of an ‘individual agent’, an approach not taken by their classical political economist predecessors, or even Keynes whose ideas followed the emergence of neoclassical economics. Modern day mainstream economists acknowledge that the economic actor exists within a social context, neoclassical logic still begins with the individual actor and superimposes onto social structure. This presupposes that actions derive from individuals and affect social structure, denying the possibility that actions can be the result of social relations themselves.

In some cases, the developments of neoclassical economics have brought the field further away from applicability to IPE. Old-school utilitarian neoclassicalism had, according to Foley (2008), a strong argument for distribution of wealth from rich to poor. The significance of marginal gains touted by the early utilitarians are of greater benefit to the poor than for the wealthy. Modern neoclassicals widely reject this, assuming it is impossible to make objective decisions of utility to individuals. This shift away from considering economic distribution across social strata represents a weakening of the relevance of neoclassical economics to IPE. As will be discussed later, understanding problems of distribution is an essential element of political economy.

Positing positivism

Neoclassical thought assumes that the goal of economic activity is the satisfaction of individual consumers and that their evaluations of the utility of goods regulates price and value (Foley, 2008). Actor behaviour is thus preference driven, a process of “maximising preference-satisfaction (Arnsperger and Varoufakis, 2006, pp.8). This understanding is problematic as the agent’s capability to question preference is removed and hence becomes a form of consequentialism. In practice, individual purchases of goods are rarely as preference maximising as theory suggests. Instead, individuals on one hand tend to consume out of habit or convenience, and on the other are forced to consume more than they would like, such as extortionate transport or rent costs. Neither can be understood from the perspective of rational satisfaction maximisers.

Yet developments in neoclassical modelling again attempt to account for such shortfalls. Neoclassical thinkers have reconsidered in recent decades ‘second order’ beliefs (Arnsperger and Varoufakis, 2006). Agent preferences are not only linked to outcomes, but also predictions of the intentions of other actors. This leads to a necessary consideration of historical and social structures surrounding interactions. Criticising neoclassical thought on its tendency to take for granted actor preferences exogenous of socio-economic relationships no longer hold, but the instrumentalist process still exists. An actor is assumed to be ends driven, even when they do not know what those ends are or how others expect them to act.

This is clear in how unused resourcesare treated in neoclassical logic.Marginalists assume all resources are utilised in the economy. Unused resources end up being considered as having a 0 price and are hence ignored. (Foley, 2008) This treatment of unused resources is highly problematic when we consider what ends up not measured within the economy. Productivity is measured only in which activity results in paid exchange. Feminist critics for example highlight how household work is consigned as ‘unproductive’ as it is unpaid. In a similar vent, unpaid internships are unproductive (Bakker, 2007; Waring, 2015).

A dynamic study in static

In attempting to model macroeconomics, neoclassical models are based on aggregates. Instrumental behaviour is organised so that aggregate behaviour appears seemingly regular and is thus reasonably predicted (2006). Questioning is focussed on what outcome is expected at equilibrium in econometric models. Whether equilibrium is likely, and how it may occur is never in doubt; it is assumed as not only an ideal, but normal condition. This presumption is then used as a basis of economic conclusions – the answers to economic problems and an accurate representation of actor behaviours (Arnsperger and Varoufakis (2006).

Equilibria may successfully model extremely narrow cases, where variables are limited and relatively controllable, but the larger a model becomes or the less controllable each variable, the less points of equilibrium can successfully model. This is because the network of interplaying behavioural and psychological factors not accounted for incrementally enlarges the margin of error.

In neoclassical economics, a pareto distribution presents a curve where all points along it represent equilibrium between possible allocations of two goods. Any of these points, where no voluntary exchange is possible and commodity prices have stabilised, is considered ‘Pareto – optimum’ (Baumol, 1998). The term is misleading as while it represents a complete allocation of available resources in a market, it masks distribution among individuals. Some actors may be far better off than others, and there is no room left for less well-off actors to improve their position. A pareto allocation is thus efficient in the eyes of neoclassical thinkers, but not necessarily socially equal (Foley, 2008).

Distribution – who gets what, where and how – is arguably the core question for political economy, even if coined by Lasswell (1935) before the formulation of IPE as a field. Consigning it to insignificance is convenient for mathematical modelling and deductive reasoning but fails in attempting to marry an understanding of states and markets collectively. Assuming the tendency of markets to clear, as Walras did (2003), underplays the reality that individuals do not always take the prices they are faced with at face value. The market clearing mechanism relies on rational actors ‘knowing’ the given price of commodities is a fair representation. Even as modern neoclassical models believe less in the rational actor with complete knowledge (Arnsperger and Varoufakis, 2006), the core concept of clearing markets only functions with those now refuted assumptions.

This article now turns to consider what effect neoclassical assumptions have on political economy conclusions.

Marginal society – Becker and behavioural economics

Honouring the marginalist dogma has not stopped every neoclassical thinker from tackling societal questions. If it were possible for neoclassical economics to effectively model social structures, then a critique based off detachment from society would be unfounded. Becker (1976) presented one of the most comprehensive attempts to do this, in the form of behavioural economics.

Becker (1976) attempts to use an ‘economic’ approach to modelling human behaviour. He argues if a definition is used that describes economics as an allocation of scarce resources to satisfy competition, then it encompasses far more than a traditional focus on markets. This would allow fields such as political processes and family dynamics to fall within the economics remit. The widely accepted definitions of economics are concerned with its subject matter, not its approach.

This standpoint suggests neoclassical economics is a methodology, not a theoretical framework. This gives some leeway for the use of neoclassical concepts within theoretical frameworks more appropriate to IPE. From this perspective, as long as a neoclassical methodology is consistent with answering a particular IPE research question it has a place within it. It is challenging to think of a situation in which a methodology void of social context would be appropriate, but it does not mean they do not exist. The modern financial sector for example is organised on neoclassical assumptions. Tackling neoclassical finance logic with the tools of neoclassical economics is thus useful.

The effectiveness of Becker’s approach in understanding social interactions is however doubtful. Becker (1976) suggests that the economic method does not assume actors are consciously aware of their self-interested profit maximising goal, consigning this to the subconscious. Becker removes variables of psychology and emotional preference with no explanation to why they are irrelevant through being unknown to the actor and thus behaviour is removed from behavioural economics. Reminding the reader of the role of the unconscious only to remove it from calculations highlights how much is inevitably missed when relying on neoclassical assumptions.

Becker is left with a more utilitarian actor, and fittingly begins his argument in ‘A theory of Social Interactions’ (Becker, 1974), with reference to Bentham (1823). Bentham’s attempt to measure human utility in terms of pleasure and pain may be an integral part of the early marginalist revolution, but elements as emotional or behavioural as pleasure and pain were dropped by his successors. Becker may have identified an early attempt to measure social interactions in the utilitarian mode, but Bentham’s approach did not become the future of marginalism. That is likely because it was a step too far logically to accept mathematical modelling of human pleasure.

Becker is also not in the same tradition as that of Bentham. Where Bentham started from social interactions, Becker reintegrates social interaction into the consumer demand base:

“Each person has a set of production functions that determine how much of these commodities can be produced with the market goods, time, and other resources available to him:

Zj = fji (xj, tj., Ei, Rj1, … Rjr)

Where xj are quantities of different market goods and services, tj are quantities of his own time, Ei stands for his education, experience, and ‘environmental’ variables, and Rji, … Rjr are characteristics of other persons that affect his output of commodities. For example, if Zi measures i’s distinction in his occupation, Rji, …Rir could be the opinions of i held by other persons in the same occupation.” (Becker, 1974, pp.4).

It is questionable how effectively some of these valuables can be reduced into a numerical value, as is necessary for the model. Variables X and T are reasonable, traditional variables, but inserting E and R within the same calculation makes little sense. Even if they could somehow be translated into numerical form, subsequently coercing that figure to hold a comparable value to variables X and T is farfetched. Schumpeter (1934) likely was correct when he suggested that economic analysis is valuable up until it must face social and psychological factors.

Neoclassical applications to hegemony and trade

Much of recent debate in IPE has turned to the socio-political implications of free trade, especially its apparent failings in the global south (Margulis, 2017). Removing consideration of distribution and relying purely on a view to efficiency has exacerbated global inequalities even as global trade has rocketed. trade is seen by neoclassical thinkers to achieve efficiency in the allocation of resources (Foley, 2008), but this comes with the neglect of societal considerations.

Some of the most influential ideas within IPE have at their roots neoclassical inspired logic. Lake (1993) explores the foundation and structure of Hegemonic stability theory and leadership theory, highlighting the neoclassical assumptions it is based on. The theories follow a positivist logic and functions under the assumption that states act as rational actors.

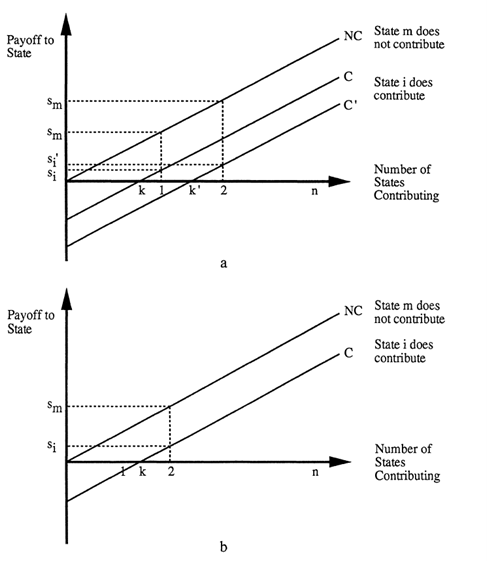

Lake challenges hegemonic stability theory with analysis from Snidal (1985) but does so using econometric methods. Utilising the notion of ‘K-groups’, he attempts to mathematically prove the possibility of more than one state producing international collective goods.

Source: Lake, 1993

This model is a perfect example of neglecting context to make the numbers work, a fact that Snidal happily admits. “This analysis ignores strategic interaction. It assumes that states are myopic decision makers and that other states’ behaviour remains constant” (Snidal, 1985, pp.600). This assumption is a critical error as states change their behaviour according to the stance of other states. Strategic interaction is not a variable that can be sensibly ignored, and suggests Snidal is more concerned with producing a certain result than accurately modelling trade. This is indeed a major issue with econometric approaches – there is much room for scholars to pick variables that present results beneficial to their own views.

This is not to suggest there no value in theorizing with such reduced models. Their use is however not in accurately representing reality, instead in following the dominant economic logic. If the major actors in an economic (or any) system adopt a certain set of beliefs, they will function in accordance with one another. The same holds for an economic system – following the main belief makes the rules function socially. while it reigns as the dominant economic theology, agents will continue to make decisions on its logic.

Lake (1993) also tackles strategic trade theory, which hypothesises that national trade policies vary because free trade fails to always maximise absolute gains. Strategic trade theory recognises that tariffs may improve national welfare if a given state has a strong domestic market. Lake does not believe this theory provides an effective foundation for international trade policy theories, claiming that most countries do not have the market power for the above situation to occur, and in reality, optimal tariffs are zero.

Universal gain from free trade is however not uncontested. In practice free trade has created massive inequalities globally as developing countries have been forced to export commodities even as their value shrinks on the international market, as argued by Raul Prebisch (Harvey et al, 2010). It is only in recent years that international organisations have begun to take this seriously and encourage developing countries to diversify away from exporting commodities (UNCTAD, 2019).

Krasner discusses neoclassical trade theory in ‘State power and the Structure of International Trade’ (1976). This theory assumes that states act to maximise their aggregate economic utility, which leads to the conclusion that global free trade offers the highest possible global welfare and achieves pareto optimality, a condition this essay has already criticised as a measure of distribution in trade. According to Krasner (1976), neo-classical trade theory acknowledges that trade policies may balance domestic pressures and support infant industry, but thinks such measures only make sense temporarily and lead inevitably to support of free trade in the long term.

Yet how temporary is temporary? In the current global economy, the split between the most and least developed countries has grown so large that it is doubtful whether any length of time pursuing defensive trade policy could bring nascent industries up to a competitive level (World Bank, 2021). In the meantime, the countries who do benefit from free trade are likely to widen the gap further.

Conclusion

This essay argued that neoclassical economics has a place in contributing to IPE arguments, but in limited situations. A sociological field assuming rational individual agents is contradictory. Equilibrium modelling oversimplifies complex socio-political relationships and assumes that points of equilibrium will A) be met and B) are the aim of concerned agents. This essay however also agrees with Cohen (2007) that the eclecticism of IPE is its strength and with Gilpin (2011) that neoclassical economics can be used in conjunction with sociological IPE approaches to draw more profound conclusions. Where neoclassical logic remains coherent to a certain question and approach, such as within the context of trade or finance, it may be fruitful to partially adopt neoclassical methods. The key shortcoming of neoclassical economics to IPE is its unconvincing management of social interactions within economic systems. Where society plays a less active role in outcomes, or when those influences are highly predictable, neoclassical assumptions are less distorting of results and can still draw meaningful conclusions.

Bibliography

Arnsperger, C., and Varoufakis, Y. (2006). What is neoclassical economics? The three axioms responsible for its theoretical oeuvre, practical irrelevance and, thus, discursive power. Panoeconomicus, 53(1).

Bakker, I. (2007). Social Reproduction and the Constitutions of a Gendered Political Economy. New Political Economy, 12(4).

Baumol, W. (1998). Utility and Value, Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Becker, G, S. (1974). A Theory of Social Interactions. Journal of Political Economy, 82(6).

Becker, G, S. (1976). The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. University of Chicago Press.

Bentham, J (1823). An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Printed for W.Pickering.

Cohen, B. J. (2007) The transatlantic divide: Why are American and British IPE so different?. Review of International Political Economy, 14(2).

Cohen, B. J. (2008). International political economy: an intellectual history. Princeton University Press.W

Fine, B. and Milonakis, D. (2009). From political economy to economics method, the social and the historical in the evolution of economic theory. Routledge.

Foley, D.K. (2008), Adam’s Fallacy: A Guide to Economic Theology. Harvard University Press.

Gilpin, R. (2011). Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order. Princeton University Press.

Harvey, D. I., Kellard, N. M., Madsen, J. B., & Wohar, M. E. (2010). THE PREBISCH-SINGER HYPOTHESIS: FOUR CENTURIES OF EVIDENCE. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(2).

Krasner, S, D. (1976). State Power and the Structure of International Trade. Cambridge University Press, 28(3).

Lake, D. (1993). Leadership, Hegemony, and the International Economy: Naked Emperor or Tattered Monarch with Potential, International Studies Quarterly, 37(4).

Lasswell. (1936). Politics; who gets what, when, how. McGraw-Hill book company.

Margulis, M. (2017). The Global Political Economy of Raul Prebisch. Routledge.

Ravenhill, J. (2017). Global Political Economy. Oxford University Press.

Schumpeter, J, A. (1934). The Theory of Economic Development: An Enquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle. Harvard University Press.

Snidal, D. (1985). The Limits of Hegemonic Stability Theory. International Organization, 39(4).

UNCTAD. (2019). Commodity-dependent countries urged to diversify exports. Available from: https://unctad.org/news/commodity-dependent-countries-urged-diversify-exports . Accessed 14 December 2022.

Walras, L., and Jaffé, W. (2003). Elements of Pure Economics: Or the Theory of Social Wealth. In Elements of Pure Economics. Taylor & Francis Group.

Waring, M. (2015). Counting for Nothing: What Men Value and What Women are Worth. University of Toronto Press.

World Bank. (2021). GDP (Current US$) – High income, Low income. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=XD-XM . Accessed 29 December 2022.