Continuing with sharing a series of pieces from my MA in International Political Economy at King’s College London in 2023, the following article was my final assessment for Dr Roberto Roccu’s ‘Political Economy of the Middle East’ module, very much a highlight of the year.

To what extent does Vision 2030 contribute to an influence shift in the Gulf from the US to China?

Close cooperation between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and China in their respective economic development strategies, KSA’s domestically focussed Vision 2030 and China’s international mega project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has sparked concerns that China is exerting a stronger grip in the gulf, to the loss of the US.

This paper attempts to merge Desai’s (2013) theories of geopolitical economy and Nye’s (1990) insights into the diffusion of power in order to analyse shifting power relations between KSA and its major partners, the US and China. This question has become increasingly important and complex as China has grown in influence and KSA has striven to raise its position on the global stage.

I argue that while China at first appears to be exerting a stronger hold on KSA, much of the power has shifted to KSA itself. In an increasingly interdependent world where a dichotomy between unipolar and bipolar systems no longer holds, states such as KSA are in a position to promote their own autonomy and not simply align with great powers. This is evident in KSA’s development strategy, Vision 2030, which orients the Kingdom towards regional power, and away from military and economic dependency.

Vision 2030 and Saudi-China relations

Vision 2030 is Saudi Arabia’s development strategy, focussed on diversifying the Saudi economy away from oil and increasing the Kingdom’s regional and international political influence. It aims to leverage the Kingdom’s geostrategic position and fully utilise its potential as a centre of trade, global value chains and regional influence. Building investment power is the foundation of Vision 2030, embodied in turning the Public Investment Fund (PIF) into the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund (KSA, 2016).

The kingdom recognises that in the long-term its dependency on oil is not sustainable. Vision 2030 therefore is heavily invested in diversification. Part of this diversification will involve a stronger shift to privatisation. The strategy is however not an end to hydrocarbons in Saudi Arabia as the strategy targets a doubling of gas production (KSA, 2016) and will continue to extract oil. The PIF plays an integral role in KSA’s development strategy, aiming to enable greater investment in domestic firms and hence help diversify KSA away from oil (PIF, 2021).

In 2017, KSA endorsed China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s flagship global infrastructure and development project, and expressed willingness to cooperate further in key sectors including trade, energy and technology. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman stated that KSA would actively participate in and cooperate with BRI developments (Chen, et al, 2018). In the first half of 2022, KSA was the largest recipient of BRI funding globally (Asharq al Awsat, 2022) and bilateral trade between KSA and China now dramatically outstrips KSA trade with the US, in 2020 amounting to US$ 65 billion compared to 20 billion respectively (MERICS, 2022).

Despite rhetoric of mutual gain, China is assertive enough to make development policy suggestions to MENA states. In a keynote speech in 2014, alongside the usual BRI infrastructure pledges, Xi Jinping proposed cooperation in aerospace programmes and satellite launches (Chen et.al, 2018), industries with doubtful immediate value to the region. Elements of BRI do coordinate well with Vision 2030. KSA wishes to build its trade capabilities but lacks the infrastructure. China wants to provide it. (Xinhua, 2016). Recent energy shortages in China show its need to widen energy supply chains (Zhao, 2022) Energy and infrastructure are at the heart of Saudi-China economic cooperation (Chen, et al, 2018).

At first glance, KSA may appear to be shifting its allegiance from the US to China. China became KSA’s largest trade partner in 2014 (Fulton, 2020) and a founding member of the AIIB in 2016 (AIIB). BRI infrastructure support is likely necessary if KSA is to progress domestic industry at the rapid rate it plans to. The opening of a PIF subsidiary in Hong Kong in February 2022 presents a degree of geostrategic positioning towards China (PIF, 2022a). KSA has however not turned away from the US. The PIF also opened a subsidiary in New York (PIF, 2022a) and the Kingdom signed a non-binding MoU with Blackrock for infrastructure funding (PIF, 2022b), potentially playing the interests of both powers off each other.

Dynamic Geopolitical Economy

This essay proposes a merging of Desai’s (2013) Geopolitical Economy with Nye’s (1990) theorizing on the diffusion and transformation of power, aiming to understand how Vision 2030 fits into global economic power relations.

Desai (2013) considers globalization as a world view envisioning global unity through nothing else than market forces. This stands in sharp contrast to the hegemonic or imperial concept of a world order through a world hegemon. Desai argues that the literature of world order has failed to strike a middle ground between the conceptualisation of globalisation and hegemonic world, neither of which explain the emerging multipolar world.

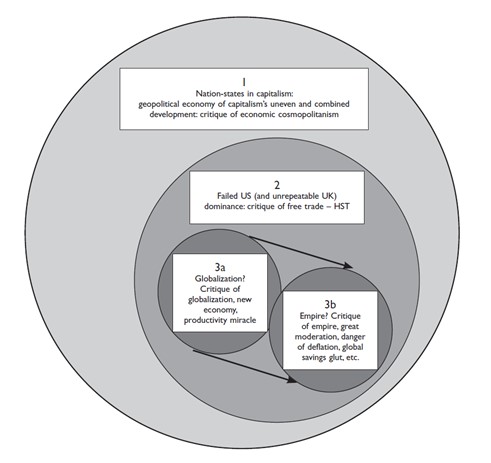

Desai thus presents a theory of Geopolitical Economy, built on three core tenets: the materiality of nations; Failed US dominance and unrepeatability of UK dominance: Globalization/empire.Desai (2013) draws on the Bolshevik concept of uneven and combined development, in which dominant states try to preserve uneven development in favour of themselves while contender states push development in order to contest imperial powers. The Post-war US restricted itself to financial influence, the US Dollar becoming the lifeblood of the international economy. She argues that the dollar as the world’s currency has been an attempt to maintain globalization and hence US hegemony. These three elements are presented below graphically:

Source: Desai, 2013.

Desai’s framework highlights how US influence is maintained by the outreach of its economic and financial power, but her theory separates this influence too far from power. As Schwartz (2019) argues, it is precisely the ‘centrality’ of the dollar which enables US influence to be so pervasive. Writing in 2013, Desai’s prediction of a diminishing dollar has not held. 10 years on, the dollar still goes strong. This is useful to understand KSA’s emphasis on building the influence of the Public Investment Fund (PIF), as will be discussed later.

The 21st century represents an end to the domination of single powers across the global system and the emergency of a multipolar order (Desai, 2013). This has come into existence through successive rounds of contender development (term coined by Van der Pijl) including the USSR and BRICS nations – groups which have spread productive power away from former imperial unipoles (Desai, 2013). The forces of geopolitical economy are those explored in Harvey’s (1981) ‘Spatial fix’. States are compelled to expand to account for falls in domestic demand, while states push back on this externalisation of domestic economies.

Using Desai’s framework, KSA is a ‘contender state’. Following this logic KSA would be expected to actively push back at dominant states to secure its own autonomy. Desai fails however to account for dynamism in state relations, a key point in understanding why KSA is only changing its stance now. Nye (1990) tackles this issue in his theorising into the diffusion of power. This does not represent a decline in power but a transformation of structure, where Nye’s theory joins with Desai’s concern with multipolarity.

Trends in 1990s world politics pointed to a world where it was increasingly challenging for any one great power to control global politics. Instead of major powers needing to tackle rising powers, politics tends towards a diffusion of power. “As world politics becomes more complex, the power of all major states to achieve their purposes will be diminished” (Nye, 1990, pp175). Politics becomes more a matter of power over outcomes and not power over countries, spreading power past state actors to private actors and transnational organizations.

Nye (1990) identifies five points that have led to a diffusion of power from states to smaller actors: Economic dependence; transnational actors; changing political issues; nationalism in weak states; and spread of technology. This essay draws on the first three points, with emphasis on the first.

Just as Desai (2013) argues state economic power relations are uneven, Nye (1990) believes that interdependence is also a form of uneven balance. Interdependence can be balanced differently depending on the issue (e.g., security, energy, trade, finance). This creates links and conflict between issues depending on the specific vulnerability of a state. This essay will consider this in terms of KSA’s oil dependency.

Analysis – a shift between poles or to autonomy?

From oil dependency to domestic industry

KSA is in many respects already a major country on the global stage. It is the 18th richest country in GDP terms (World Bank, 2021) and the largest country geographically in the GCC. It is also the lead country in OPEC and has the second largest proved oil reserves globally (OPEC, 2021). Its oil power has historically however also been KSA’s greatest vulnerability. Hydrocarbons are a finite resource, and when they dry up, oil revenue ends. Oil has held KSA in a dependency relationship with the US for decades, providing the US with dominant political leverage over the Kingdom. As KSA attempts to grow other sectors, the US economic stranglehold loosens.

Without a robust domestic economy, states become dependent on trade imports. KSA has long imported US military equipment, a dependency it plans to reduce through Vision 2030 (KSA, 2016). This move represents a dramatic shift in KSA’s potential economic and hard power. Shifting production domestically creates new non-oil industry and reduces import costs. The improvement to manufacturing infrastructure will also ease barriers to growth in industry outside of military purposes. Geopolitically speaking, KSA will gain more autonomy in its defence manoeuvring.

This does not represent a shift between the global political poles of the US and China, but a strengthening of KSA’s own autonomy. KSA intends to maintain its hydrocarbon production (KSA, 2016), but the goal is not to shift its oil dependency onto an increasingly welcoming China.

Security collaboration with China remains at a low level. Fulton (2020) argues that this is because China can’t be seen to challenge the US security arrangements in the Gulf. Yet Fulton assumes China has a military interest in the Gulf, an assumption with little grounding.

KSA as a contender state

Freeing itself from oil interdependency reveals KSA as a contender state (Desai, 2013; Van der Pijl, 2012). The Kingdom is however asserting its position less in line with Desai’s understanding of uneven development and more aligned with Nye’s (1990) diffusion of power. KSA is actively positioning itself but is doing so through leveraging international systems and the increasing power of international money flows.

These interests are spread globally, not only towards the US, in what Fulton (2020) refers to as strategic hedging. International investments include in Japan’s Softbank, Lucid Motors in the US, Russian and French investment funds and Indian Telecom firm Jio (PIF, a). The PIF has also entered into joint ventures, namely with Taiwan’s Foxconn, aimed at creating KSA’s first electric vehicle brand (PIF, 2022c). KSA made investments in US equities totalling US$ 7.6 billion in Q2 of 2022 alone, focussing on tech megafirms such as Alphabet and Zoom (The National, 2022). In doing so, KSA is diversifying its influence structure and hedging dependency.

The immediate catalyst for KSA’s emergence as a contender state is its depleting oil reserves. Yet the Kingdom needed past oil revenue in order to initiate the PIF that will power its next stages of growth. Looking forwards, KSA must diversify, and previously it was restricted by its narrow industrial structure.

Building international trade and finance influence

Desai (2013) and Schwartz (2019) argued that it is financial power -dollar centrality – that provides the US with its global influence. The logical extension of this theory is that any state can improve its global position by growing its global financial networks. The PIF is presented as a means of rapidly growing KSA’s domestic economy (PIF, 2021), but it also plays into future structures of political influence.

The PIF has developed with an aim of transferring oil wealth into a more sustainable domestic economy. To do that, KSA must turn its formidable capital into a modern productive economy. This is where infrastructure development is essential and where the importance of the BRI is clear. In December 2022, bilateral projects worth US$ 1 billion were signed for at the first China-Gulf Cooperation Council summit in Riyadh (Zawya, 2022). Chinese infrastructure investments currently focus on strategic port locations at Jizan and Jubail Industrial Cities (SSRIS), which fit directly into the maritime trade route part of China’s BRI plans.

Trade interdependence is a two-way process. While there is an element of political leverage present within state backed FDI, KSA has leverage over China in whether it cooperates or not. Influence structures built off trade networks inherently diffuse power. The result is that while China is increasing its stake in Gulf business, KSA loses little autonomy.

Nye (1990) highlights the increasing importance of ‘intangible resources’ a concept he later developed into ‘soft power’ (Nye, 2004). Universalistic culture, national cohesion, and international institutions are increasingly important, and power becomes increasingly attributed to the ‘information-rich’ over the ‘capital-rich’.

The PIF is being utilised as a means of transferring abundant capital into a nascent information economy. Domestically, the majority of PIF investment has angled towards the finance sector including private investment companies, and infrastructure firms (PIF, b) but many of these private investors are focussed on growing KSA’s technological and industrial sectors.

KSA’s custodianship of the Hajj and its increasing investment in it as a form of pilgrim tourism represents a transformation of capital into both revenue generation and soft power, a point presented as a core element in the Vision 2030 strategy (KSA, 2016). Prior to the Global Coronavirus pandemic in 2018, Mecca attracted US$ 20 billion in tourist dollars, and was forecast to reach 30 billion in 2022 (CNN, 2022).

These two above points have little role in aligning with any major power. Instead they solidify KSAs role as its own regional power, with economic and cultural forces that create a pulling force towards it internationally.

Conclusion

While US influence in KSA is dissipating this does not represent a shift in alignment from one global pole to another. China is heavily invested in KSA but does not control the same degree of leverage the US-Gulf security agreements ensured in the past. An increasingly multipolar world has offered KSA more than a choice between global powers old and emerging. A global diffusion of power results in conditions for contender states such as KSA to carve their own path to greater autonomy on the global stage. This is within constraints. The forces of globalization have led to a world order characterised by economic interdependence, where states are forced to share their power with increasingly influential private actors, and financial power is as important as brute military force.

Bibliography

AIIB. (2016). Members of the Bank. Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank. https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/governance/members-of-bank/index.html. Accessed 20 December 2022.

Asharq al Awsat. (2022). Saudi Arabia receives largest share of China’s BRI investments. https://english.aawsat.com/home/article/3780171/saudi-arabia-receives-largest-share-chinas-bri-investments . Accessed 20 December 2022.

Chen, Juan ; Shu, Meng ; Wen, Shaobiao. (2018). Aligning China’s Belt and Road Initiative with Saudi Arabia’s 2030 Vision: Opportunities and Challenges. China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies.Vol.4 (3), p.363-379

Lawati, A, B. (2022). The Hajj is back and Saudi Arabia is hoping to cash in. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/06/business/saudi-hajj-economy-mime-intl/index.html . Accessed 20 December 2022.

Desai, R. (2013). Geopolitical economy: after US hegemony, globalization and empire. Pluto Press.

Fulton. (2020). Situating Saudi Arabia in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Asian Politics and Policy, 12(3).

Harvey, D. (1981). THE SPATIAL FIX – HEGEL, VON THUNEN, AND MARX. Antipode, 13(3), 1–12.

KSA. (2016). Vision 2030. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The National. (2022). Saudi Arabia’s PIF tops up the stakes in US stocks with $7.6bn of new investments. https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/markets/2022/08/16/saudi-arabias-pif-tops-up-stakes-in-us-stocks-with-76bn-of-new-investments/. Accessed 20 December 2022.

OPEC. (2021). Saudi Arabia facts and figures. https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/169.htm. Accessed 20 December 2022.

PIF. (2021). Annual Report 2021. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund.

PIF (2022a). PIF opens three new subsidiary company offices in London, New York, and Hong Kong as fund continues expansion globally. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund. https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/Pages/NewsDetails.aspx?NewsId-208/PIF-OPENS-THREE-NEW-SUBSIDIARY-COMPANIES-OFFICES-IN-LONDON-NEW-YORK-AND-HONG-KONG-AS-FUND-CONTINUES-EXPANSION-GLOBALLY. Accessed 20 December 2022.

PIF. (2022b).PIF signs MoU with Blackrock to explore infrastructure investments in Saudi Arabia and the Middle East. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund. https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/Pages/NewsDetails.aspx?NewsId-227/PIF-signs-MoU-with-BlackRock-to-explore-infrastructure-investments-in-Saudi-Arabia-and-the-Middle-East. Accessed 20 December 2022.

PIF. (2022c). HRH Crown Prince launches CEER, the first Saudi electric vehicle brand. https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/Pages/NewsDetails.aspx?NewsId-224/HRH-CROWN-PRINCE-LAUNCHES-CEER-THE-FIRST-SAUDI-ELECTRIC-VEHICLE–BRAND . Accessed 20 December 2022.

PIF. (a). International Investments. https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/Pages/OurInvestments-Global.aspx . Accessed 20 December 2022.

PIF. (b). MENA Investments. https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/Pages/OurInvestments-Local.aspx. Accessed 20 December 2022.

MERICS. (2022). Saudi Arabia’s once marginal relationship with China has grown into a comprehensive strategic partnership. Mercator Institute for China Studies. https://merics.org/en/saudi-arabias-once-marginal-relationship-china-has-grown-comprehensive-strategic-partnership#:~:text=In%20turn%2C%20Saudi%20Arabia%20has,production%20capacity%20for%20Saudi%20producers . Accessed 20 December 2020.

Nye, J. (1990). Bound to lead: the changing nature of American power. Basic Books.

Nye, J. (2004). Soft power: the means to success in world politics. Public Affairs.

Schwartz, H. M. (2019) ‘Economic and Hegemonic Cycles,’ in States versus Markets: Understanding the Global Economy, pp. 61-78

SSRIS. Company Profile of SSRIS LLC. Saudi Sil Road Industrial Services. http://www.saudi-silkroad.com/en/about/index.aspx. Accessed 20 December 2022.

Van der Pijl, K. (2012). Is the East Still Red? The Contender State and Class Struggles in China, Globalizations, 9:4, 503-516,

World Bank. (2021). GDP (Current US$). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?most_recent_value_desc=true. Accessed 20 December 2022.

Xinhua. (2016). China’s Arab Policy Paper. http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/publications/2016/01/13/content_281475271412746.htm. Accessed 20 December 2022.

Zawya. (2022). BRI: China and Saudi Arabia to cooperate on 7 projects worth $1bln. https://www.zawya.com/en/projects/bri/bri-china-and-saudi-arabia-to-cooperate-on-7-projects-worth-1bln-reje2lhg . Accessed 20 December 2022.

Zhao, Z. (2022). China’s Power Crisis: Why is it happening and what does it mean for the economy?. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3190313/chinas-power-crisis-why-it-happening-and-what-does-it-mean . Accessed 29 December 2022.