What on earth does an English language notetaking method designed for reporters have in common with Arabic or Chinese script?

Quite a lot, it turns out. Take it from the language enthusiast writer.

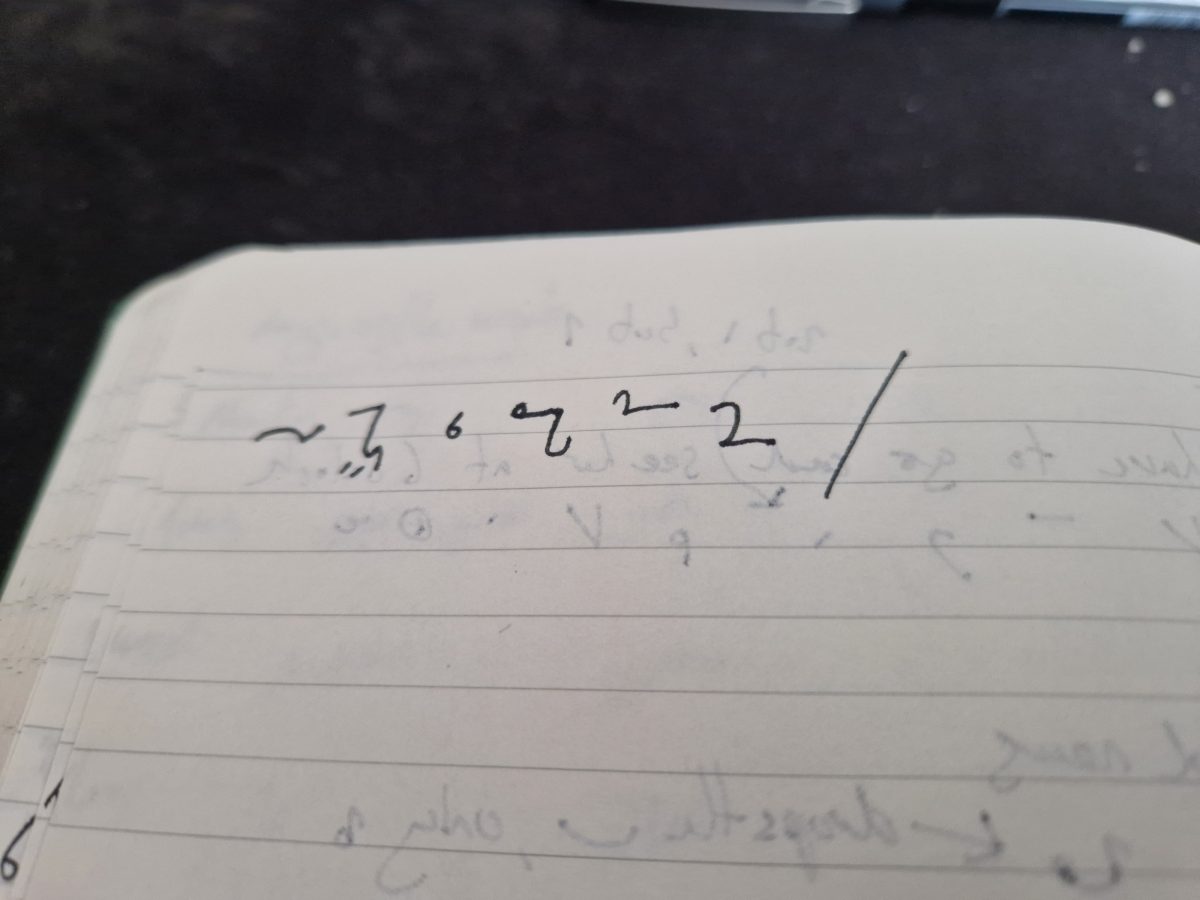

Last weekend I decided to teach myself Teeline. How you learn a skill in three days that News Associates allocates a whole 20 weeks study for, is covered in my last article, found here.

Teeline and Arabic

Teeline is an abjad script. That means that whenever possible, vowels are omitted. To anyone not used to the idea it could be hard to imagine how it is possible to understand a script with no vowels in, but it certainly works.

Less ‘noise’ can even be a good thing eventually. The key value for Teeline is that omitting letters speeds up the writing process and takes less space on the page.

Aesthetically, dropping vowels can make a script more attractive. Arabic script in my view is stunningly beautiful, but if you add in every single vowel it quickly becomes unwieldy. Some Turkic languages (at least the ones still using Arabic script, Turkish not being one of them since 1928) write out every vowel, and words become ever harder to read.

For some languages, Abjads are a very good idea.

Discovering this weekend that English can be written as an abjad was a real eye-opener. I thought of all my friends and acquaintances who have had to learn English as a foreign language, and the horror that is English spelling convention.

I must ask myself, maybe English should be written as an abjad.

That’s not a suggestion I’ll be pushing but it is fascinating to see English writing streamlined by removing much of the information in each written word.

The UK is bad enough at learning second languages to request it learn its own language again.

Teeline and Chinese characters

I’m sure some of the linguists out there may, with a little hesitancy, support my claim that Teeline and Arabic have some common ground.

‘Teeline is like Chinese’ might anger a few people though. Hear me out.

Chinese characters are not phonetic. There is no Chinese alphabet. That tattoo artist telling you otherwise was lying to you, and you may now have ‘Lanzhou beef noodles’ inscribed on your back instead of your nickname.

Teeline is phonetic, but the letters can be abbreviated so far that they take on more symbolic value. While most of these ‘special outlines’ relate phonetically to the world they represent, the connection can get blurred.

On one hand, A Teeline ‘K’ can stand for ‘King’ – an obvious link. On the other hand, A Teeline ‘C’ written under a page line can stand for ‘local’. The importance of position on the page also brings the symbol a little further from pure phonetics and a little closer to an ideograph.

I am still very new to the abbreviation element of Teeline, but these more symbolic examples struck me as similar to Chinese. After all, the evolution of Chinese characters is also a story of abbreviation and simplification. The most ancient characters had a much stronger resemblance to the objects they represented. Over time, simplification has chipped away at that connection.

What does this mean for using Teeline?

Ultimately, Teeline was designed for a specific purpose and its similarities to other scripts are just oddities.

But it is interesting when elements of other writing systems generally deemed challenging to learners suddenly show their utility. The lack of vowels in Arabic and the ambiguity that follows is intimidating on the first steps of an Arabic learning journey.

Likewise with Chinese, a non-phonetic writing system can seem ridiculous to learners at first, but characters have the power to compact huge amounts of information into a tiny space – just as those Teeline special outlines do.

As a lover of languages and writing, its brilliant to see the two worlds converge in unlikely ways – and learn a thing or two along the way.

(This is an AI-free article. My content is all-human written, unless stated otherwise.)