So not only is today the first anniversary of the blog, but this will be post number 100! I think I can safely say that I’ve finally made a fairly good grounding for ‘thoughtofVG’, so without further ado, onto my 100th post.

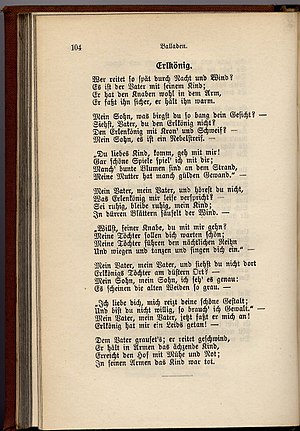

Today, I’m exploring the work of a magical writer, that most native English speaker will no doubt have heard heard of, but most will not have had the joy of knowing his work – at least, written in it’s original German. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. I’ll begin by saying that the first time I read a Goethe poem, it was an English translation of ‘Der Erlkönig‘, or in English ‘the Erlking‘. Truth is, it’s an incredible poem, having even been turned into dramatic, heart-thumping opera music, but in English it had lost it’s power and to be completely honest, wasn’t very good. In this post, i’ll be exploring his poem ‘Mailied’, providing you all with the original German and my translation into English, then analysing the poem to reveal it’s true genius.

Mailied

Wie herrlich leuchtet

Mir die Natur!

Wie glänzt die Sonne!

Wie lacht die Flur!

Es dringen Blüten

Aus jedem Zweig

Und Tausen Stimmen

Aus dem Gesträuch

Und Freud und Wonne

Aus jeder Brust.

O Erd, O Sonne!

O Glück, O lust!

O Lieb, O Liebe!

So golden schön,

Wie Morgenwolken

Auf jenen Höhn!

Du Segnest herrlich

Das frische Feld,

im Blütendampfe

die volle Welt.

O Mädchen, Mädchen,

Wie lieb ich dich!

Wie blickt dein Auge!

Wie Liebst du mich!

So liebt die Lerche

Gesang und Luft

Und Morgenblumen

Den Himmelsduft

Wie ich dich liebe

Mit warmen Blut,

Die du mir Jugend

Und Freud und Mut

Zu neuen Liedern

Und Tänzen gibst

Sei ewig glücklich,

Wie du mich Liebst!

Song of May

How gloriously shines

Nature to me!

How the sun gleams!

How the open field smiles!

The blossom forces

Out of every branch

And a thousand voices

Out of the bush

And joy and bliss

Out of every breast

Oh Earth! Oh Sun!

Oh joy! Oh desire!

Oh love! Oh lover!

So beaut’fully gold,

How morning winds

Up at those heights!

You gloriously bless

The fresh field,

In blossom-mist

The whole world

Oh Lady, Lady,

How I love you!

How your eyes look!

How you love me!

So love the larks

The song and the air

And morning flowers

The heaven’s scent

How I love you,

With warm blood,

That you bring me youth

And courage and joy

To new songs

And dancers give

Be blessed Happy

As you love me!

As you can see, i made no attempt to keep the rhyme pattern, and little attempt to keep the rhythm, but what’s important is that those of you who don’t know German you can now understand at least what the words mean! (except for the one or two translation mistakes i’ve no doubt made..) Unfortunately, by translating it, alot of the genius of the poem is lost, but i will at least be able to show some of that in my analysis.

Goethe is renowned for his mastery of form, and this is clear in ‘Mailied. It is arranged in a very distinct yet different meter, that I actually have no idea what it is, but holds firmly throughout the poem, elegantly keeping the poem flowing. even the lines where excessive exclamation marks are used, “O Erd! O Sonne!, O Glück! O Lust! (oh earth! oh sun! oh joy! oh desire!)” flows along without much hindrance to the flowing rhythm. The rhyme however isn’t so strict, some stanzas rhyming lines 1 and 3, others rhyming 2 and 4 and some only containing half-rhymes. Interestingly, this style of rhyme scheme doesn’t detract from the strict form of the rhythm, but rather adds to it. It contributes a sense of freedom that is only added to by the strong yet gently stress patterns. this freedom and lulling nature works perfectly for the themes of nature and love that run through the poem, and perhaps their differing yet intertwining natures mirror the relationship between the themes.

Perhaps the most interesting point about the structure of ‘Mailied’ is lost in translation. Notice how in German, the first and last lines end begin with the word ‘wie’. This word has multiple purposes in German and can act as both an exclamatory word (how….!) or as a comparative word (like). When translating, I had to choose which meaning i considered more important, as it actually has the power to completely change the meaning of the poem. I chose to translate it as a comparative. This way, the poem is the speaker comparing his lover to the beauty and wonder of nature, and I believe is the most widely accepted view. However, if we translate the final ‘wie’ of the poem as an exclamatory word, we could consider all the imagery of a woman to be a metaphor, as nature becomes described as a woman rather than woman being described in terms of nature. One could also argue that both meanings are intended. After all, Goethe was very careful in the words he chose, always using words that perfectly fit their situation, which leads onto a later point I will make.

Now let us discuss the imagery in the poem that describes nature in human terms. Even as early as the very first stanza there is a suggestion of this in the line “wie lacht die Flur! (how the open field smiles!)”. Describing a scene from nature as a facial expression gives us our first glimpse that nature’s attributes are being used to describe a person, supporting that the ‘wie’ we explored earlier is being used in its comparative form. One could however still argue that it actually nature being personified, the large expanse of a ‘Flur’ being used to emphasise that it is nature as a whole which metaphorically smiles at the poet. Goethe certainly was fascinated by nature, so this view finds support in the way Goethe describes nature in many of his other poems. A second person (or personified nature) other than the speaker is only clearly introduced in stanza 5 with the introduction of “du” instead of “es”; “Du segnest herrlich (you bless gloriously)”. There is no doubt after this point in the poem whether there is another figure, be it nature as a person, or a lover. The feminine imagery continues in this stanza with “Das frische Feld, im Blütendampfe (the fresh field in the blossom-mist)”. As seen earlier, the fields could be seen as the whole of nature, and this was given human attributes by smiling. “das frische Feld” here could therefore be seen as a woman and its “Blütendampfe” as her sweet scent or perfume. This repeated combined and interchangeable imagery creates a mutual respect between the beauty of nature and a woman, helped and emphasised by the dual meaning of the word “wie”. What begins to become strikingly clear is how intertwined each and every technique used by Goethe in the poem is.

One word is, I personally feel, an anomaly in ‘Mailied’: “dringen ( to penetrate/force). The entire poem is other than this lone word is both graceful and gentle, yet dringen is a harsh word with a harsh and forceful meaning, seemingly having no place in the calm nature of the poem. Everything is done with such ease other than the blossom ‘forcing’ it’s way out of the branches, so why such a strong word? The answer lies later in the poem in the already discussed lines “Das frische Feld im Blütendampfe”. If the “Blütendampfe” is the scent or presence of the woman of the poem, the blossom forcing its way from the branches is surely the inescapable presence and force of the woman (or nature, depending on your interpretation). The passion of the language in which the speaker describe the lover shows this inescapable force; “Wie ich dich liebe mit warmen Blut, die du mir Jugend und Freud und Mut”

And finally, allow me to talk about the actual title of the poem, which is of course incredibly important too. ‘Mailied’ or ‘song of may’ in english, explains exactly what state of nature the woman is being compared to. Spring; the time of life returning to nature, of energy, of rejuvenation. These attributes can be used to describe the passion of new love as well as the life giving season, and for me, this makes the overruling theme an actual woman rather than a metaphor for nature. Although the title refers to a season and therefore nature itself, the nature of the month perfectly describe love and hence the passionate relationship between poet and lover.

So there you go. You can enjoy a translated poem or text, but you’ll miss out on the true beauty and genius which goes on in the background. Thanks for reading, and remember, as is said in one of the old star trek films (don’t quote me, i’m not a big star trek fan), You can’t appreciate Shakespeare until you’ve heard it in the original klingon.

Skip to content